“It may take three years, it may take five, but whatever happens we’ll come back for you”, this were the words that he had believed & for his belief the commander had to return to take him home.

This is the story of Hiroo Onoda, the Imperial Japanese Army officer who fought in World War II & was a Japanese holdout who did not surrender at the war’s end in August 1945, he remained at his jungle post on an island in the Philippines for 29years, refusing to believe that World War II was over, until his former commander traveled from Japan to formally relieve him from duty by order of Emperor in 1974.

|

| Hiroo Onoda, before & after holdout |

Onoda was born on March 19, 1922 in Wakayama prefecture, central Japan. At 17 he went to work for a trading company in Wuhan, China, which Japanese forces had occupied in 1938. In 1942 he joined the Japanese army, was signed out for special training, and attended Nanako School, the army’s training center for intelligence officers. He studied guerrilla warfare, philosophy, history, martial arts, and propaganda & convert operations there.

On 26 December 1944, he was sent to Lubang Island in the Philippines, was ordered to do all he could to hamper enemy attacks on the island, including destroying the airstrip to disrupt a coming American invasion and the pier at the harbor. Onoda’s orders also stated the under no circumstances was he to surrender or take his own life. But superior officers on the island superseded those orders to focus on preparations for a Japanese evacuation. When American forces landed on Feb28, 1945, within a short time of landing all but Onoda & three other soldiers had either died or surrendered. At that time Yoshimi Taniguchi, gave Lieutenant Onoda his final orders, to stand & fight. “It may take three years, it may take five, but whatever happens we’ll come back for you”, the major promised. Onoda, who had been promoted to Lieutenant, ordered the man to take to the hills. Loyal to a military code that taught that death was preferable to surrender, he remain behind on Lubang Island, 93 miles southwest of Manila, when Japanese forces withdrew in the face of an American invasion.

After Japan surrendered, that September, thousands of Japanese soldiers were scattered across China, southwest Asia & the Western Pacific. Many stragglers were captured or went home, while hundreds went into hiding rather than surrender or commit suicide. Many died of starvation or sickness. A few survivors refused to believe the dropped leaflets & radio announcements saying the war had been lost.

Lieutenant Onoda, the intelligence officer trained at guerrilla tactics, with three enlisted man, Yuichi Akatsu, Shoichi Shimada & Kinshichi Kozuka, continued their campaign as Japanese holdouts living in the mountains of Lubang Island, during which they got involved in several shootouts with police, assuming them enemies. 1st time they found leaflets proclaiming the Japan’s surrender & war’s end was in October 1945, but they believed it to be enemy propaganda. They build bamboo huts, pilfered rice & other food from a village & killed cows for meat; they were tormented by tropical heat, rats & mosquitoes & they patched their uniforms & kept their rifles in working order. After a incident of killing a cow for meat they found a leaflet left behind by the islanders “The war ended on 15 August. Come down from mountains!” they concluded it to be another enemy propaganda & also believed that they would not have been fired on if the war had indeed been over. Toward the end of 1945, leaflets were dropped by air with a surrender order printed on them from General Tomoyuki Yamashita of the Fourteenth Area Army. They had been in hiding for over six months, and this leaflet was the only evidence they had the war was over. Onoda's group studied the leaflet closely to determine whether it was genuine, and decided it was not.

Yuichi Akatsu, one of the four surrendered to Filipino forces in 1950 after six months on his own. This seemed like a security problem to the others and they became even more cautious. In 1952 letters and family pictures were dropped from aircraft urging them to surrender, but the three soldiers concluded that this was a trick. On 7 May 1954, Shimada was killed by a shot fired by a search party looking for the men. Kozuka was killed by two shots fired by local police on 19 October 1972, when he and Onoda, as part of their guerrilla activities, were burning rice that had been collected by farmers. Onoda was now alone.

|

| Norio Suzuki with Onoda |

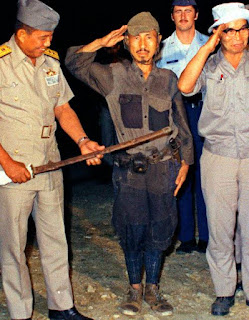

The last holdout, lieutenant Onoda officially declared dead by 1959, was found by Norio Suzuki, a student searching for him in February 1974. Onoda described this moment in a 2010 interview: "This hippie boy Suzuki came to the island to listen to the feelings of a Japanese soldier. Suzuki asked me why I would not come out ...” The lieutenant rejected Suzuki’s pleas to go home, insisting that he was still waiting for superior orders. Suzuki returned to Japan with photographs of himself and Onoda as proof of their encounter, and the Japanese government located Onoda's commanding officer, Major Yoshimi Taniguchi, who had since become a bookseller, to relieve him from duty formally. Taniguchi flew to Lubang, and on 9 March 1974, he finally met with Onoda and fulfilled a promise he had made back in 1944: "Whatever happens, we'll come back for you". In Manila, the lieutenant, wearing his tattered uniform, presented his sword to President Marcos & turned over his functioning Arisaka Type 99 rifle, 500 rounds of ammunition and several hand grenades, as well as the dagger his mother had given him in 1944 to kill himself with if he was captured.

|

| When he finally believed that japan has surrendered |

Although he had killed people and engaged in shootouts with the police, the circumstances (that he believed that the war was still ongoing) were taken into consideration, and Onoda received a pardon from President Ferdinand Marcos.

|

| Returning from Lobang |

Onoda was so popular following his return to Japan that some people urged him to run for the Diet. He was already a national hero when he arrived in Tokyo, met by his aging parents & a huge flag-waving crowd. More than patriotism or admiration for his grit, his jungle saga, this had dominated the news in Japan for days, evoked waves of nostalgia and melancholy. In an editorial, The Mainichi Shimbun, a leading Tokyo newspaper, said: “To this soldier, duty took precedence over personal sentiments. Onoda has shown us that there is much more in life than just material affluence & selfish pursuits. There is the spiritual aspect, something we may have forgotten.” He also released an autobiography, “No Surrender: My Thirty-Year War”, shortly after his return, detailing his life as a guerrilla fighter in a war that was long over. The Japanese government offered him a large sum of money in back pay, which he refused. When money was pressed on him by well-wishers, he donated it to Yasukuni Shrine.

|

| The soldier finally came back to his homeland as a national hero |

Though his story went global in books, articles & documents, he tried to lead a normal life. He took driving lessons, travelled in Japanese islands but he found himself a stranger in strange land, disillusioned with materialism & overwhelmed by changes. Onoda was unhappy with being the subject of so much attention and was troubled by what he saw as the withering of traditional Japanese values. After struggling to adapt to life in his homeland, he immigrated to Brazil in 1975 to become a farmer. He married Machie Onuku in 1976 and assumed a leading role in Colônia Jamic (Jamic Colony), the Japanese community in Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. After reading about a Japanese teenager who had murdered his parents in 1980, the couple returned to Japan in 1984 and established the Onoda Shizen Juku ("Onoda Nature School") educational camp for young people, held at various locations in Japan.

|

| Mr. Onoda showing a picture of himself taken when he surrendered |

Onoda revisited Lubang Island in 1996, donating US$10,000 to the local school there. His wife, Machie Onoda, became the head of the conservative Japan Women's Association in 2006. For many years, he spent three months of the year in Brazil. Onoda was awarded the Merit medal of Santos-Dumont by the Brazilian Air Force on 6 December 2004. On 21 February 2010, the Legislative Assembly of Mato Grosso do Sul awarded him the title of Cidadão ("Citizen").

The cave of Lubang where he stayed for 29 years as Japanese holdout has now become a traveler’s destination of Philippines. The people of Lubang express mixture of emotions towards Onoda, some considering him a historical hero of Japan, others considering him a villain for murdering of their relatives.

Onoda died of heart failure on 16 January 2014, at St. Luke's International Hospital in Tokyo, due to complications from pneumonia. Japanese Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga commented on his death: "I vividly remember that I was reassured of the end of the war when Mr Onoda returned to Japan" and also praised his will to survive.

Japanese history & literature are replete with heroes, who have remained loyal to a cause, especially if it is lost or hopeless, and lieutenant Onoda, a small, wiry man of dignified manner & military bearing, seemed to many like a samurai of old, ultimately offering his sword after almost 30 years, as a gesture of surrender to President Ferdinand E. Marcos of the Philippines, who returned it to him.

He was one of the war’s last holdouts: a soldier who believed that the emperor was a deity & the war a sacred mission; who survived on Bananas & coconuts & sometimes killed villagers he assumed were enemies; who finally went home to the lotus land of paper & wood which turned out to be a futuristic world of skyscrapers, television, jet planes & pollution & atomic destruction

And his homecoming, with roaring crowds, celebratory parades & speeches by public officials, stirred his nation with a pride that many Japanese had found lacking in the postwar years of rising prosperity & materialism. His ordeal of deprivation may have seemed a pointless waste to much of the world, but in Japan it was a moving reminder of the redemptive qualities of duty & perseverance.

By- Primavera

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hiroo_Onoda

https://amp.theguardian.com/world/2014/jan/17/hiroo-onoda-japanese-soldier-dies

By- Primavera

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hiroo_Onoda

https://amp.theguardian.com/world/2014/jan/17/hiroo-onoda-japanese-soldier-dies

Comments

Post a Comment